The idea of ‘troubling care’ has been conceptualized by feminist scholars such as Ann Bartos (2018) and Parvati Raghuram (2016), calling us to consider the complex ways in which care is practiced, experienced, and understood. Academics, community benefit organizations, artists, activists, caregivers, and a range of other actors are doing this work by complicating what care means and re-imagining how it is practiced.

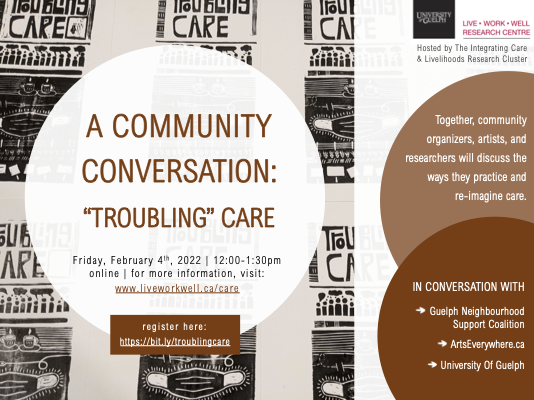

This conversation featured a panel of practitioners and scholars who are engaged in the practice of “troubling care.” Panelists’ discussed their everyday experiences and understandings of care, the practices they use to “trouble care,” and their visions for more caring futures.

Panelists included folks from the Guelph Neighbourhood Support Coalition (GNSC), Arts Everywhere's Complicating Care Series, and the University of Guelph.

A Community Conversation: “Troubling Care” Event Summary

The panelists of this event included:

Nasra Hussein (she/her): Nasra identifies as a s Somali Canadian, Muslim, Black woman. She works as a health equity lead at the Guelph Neighbourhood Support Coalition. She is a community organizer with Black Lives Matter Guelph and works with the City of Guelph on their anti-racism community plan.

Kevin Sutton (they/them): Kevin is of first generation Black West Indian heritage. They are a community resilience facilitator at the Guelph Neighbourhood Support Coalition, an activist and community organizer, a poet, performer, and an artist.

Sonali Menezes (she/her): Sonali’s background is South Asian from India. She is an artist based in Hamilton and attended the University of Guelph.

Elisabeth Militz (she/her): Elisabeth is a postdoctoral research fellow in the Department of Geography at the University of Guelph. She is a White German feminist geographer. Her work has brought her to many countries, including Azerbaijan, Kyrgyzstan, Switzerland, the United States and now Canada.

What is Care?

According to Maria Puig de la Bellacasa in Matters of Care (2017), care can be a moral obligation, work, a burden, joyful, something we can learn or practice and something we just do. Care means all these things and different things to different people, in different situations. This conversation dug into the complexities of care, with a focus on how care is troubled, and what troubling care looks like in communities and academic practices.

1) What is an object, place or activity that represents care to you?

What represents care for Nasra is community. She discussed how growing up Muslim and a first generation Somali Canadian, it was important for her family to connect with both the Somali and the Muslim communities.

An object of care for Kevin is their sleeping companion Smarsh (a squishmallow). Kevin explained that when they pull Smarsh to their chest, it feels like being given a comforting hug.

For Sonali, tea represents care. Growing up with her family, each morning began by one family member making tea for the rest of the family.

Elisabeth described her phone as her method of caring. As a travelling researcher, her phone allows her to be transnationally connected to her family, friends, and colleagues.

2) Describe how you define and understand care and practice it in your own lives.

Nasra describes care as being very subjective, and as meaning something different to each person. It goes beyond the physical, such as needs met with food, water, and shelter, and is associated with the needs of the heart, mind, and spirit, such as belonging to a community and feeling loved. Nasra understands the physical and non-physical parts of care as intersecting to create a sense of safety and self-actualization. Nasra practices care through love languages, such as words of affirmation, quality time, physical touch, acts of service, and receiving gifts. Narsa explained how she practices care this way by engaging with her community, spending time with the people she loves, and sharing intimate moments with them.

To Kevin, we are all part of one giant biosphere, intimately connected as one organism. Care in this sense is a state of being rather than a specific interaction. It is the context in which we’re living. Kevin describes how care and justice are inextricable from one another. That is, care is treating others with fairness, empathy, and reciprocity. Kevin believes that there needs to be a balance between care and justice in order for us to truly care for one another. This balance should revolve around consent and healthy boundaries. Kevin practices care by making room to care for others. They describe this as shifting their focus away from their own needs in a given moment and taking into account the needs of others.

Similar to Nasra, Sonali also connects love languages with care, including especially acts of service, physical touch and quality time. For instance, during the pandemic, Sonali created a zine (a zine is a collection of art, poems, and/or writing) of cooking recipes and offered it to family, friends, and members in her community in hopes that it would meet someone else's needs and resonate with them. Sonali’s zine is how she is trying to enact care at a distance throughout the pandemic. She explains that she struggles with not physically being there for friends and family during the pandemic, and so her zine is her way of offering her care in a different way at a distance.

As a feminist geographer, Elisabeth takes an academic approach to care. She defines care as attuning to others, such as the people in her department, in her neighbourhood, and even people at the supermarket she may not know. Care to Elisabeth also includes attuning to nature, such as the ground, the animals, the weather and other surroundings. Elisabeth practices care by mobilizing her privileges as an academic, including the specific knowledge and experiences she has, to empower others. Elisabeth seeks to create an academic environment that is welcoming to people who have been underrepresented. She does so by listening and connecting with people who have different experiences to increase collaboration in academic environments and remove the competition that divides people in these settings.

3) What does troubling, reimagining or complicating care mean to you, and what has this looked like in your practice, your work?

Nasra relates troubling care to the term “health care”, stating that we have created a health care system that often sees patients as numbers who go in and out of doors, and that lacks empathy, compassion, and care. Nasra reflected on her parents who immigrated from Somalia and have experienced cultural and language barriers from the health care system for years. She stated that health care professionals often do not listen to her parents' concerns, and instead treat visits as a procedure that starts and ends in the span of ten minutes. Nasra stated that this is not what care is or should be. Instead, care should be person-centered and compassionate. This includes linking individuals to health services but also social and community supports that empower individuals and communities to build their self-determination.

Troubling care to Kevin revolves around justice, fairness, empathy, reciprocity, and the process of connecting with one another. Kevin asked, “how do you care for someone who doesn’t care? How do you care for folks with whom reciprocity is non-existent?” Kevin discussed a care scale people move through during their lives stating that sometimes people are care-free and not worried about anything. Other times people are care-filled and sacrifice their own care to make sure those around them are cared for. Occasionally people are care-ful, where they don’t feel safe and are more tender. And people can also be care-less and withdrawn from others. Kevin troubles care by reflecting on those spaces where people are care-less to imagine ways to overcome this to create community cohesion centered around justice.

When Sonali thinks about troubling care, she thinks about challenging the liberal capitalist self-care model. Sonali expressed that there is this idea where people think about the individual as the most important unit in society. Here, the most important thing for each of us is to first and foremost care for ourselves, but in the liberal self-care model this is often at the expense of others and does not create space for others. Therefore, when thinking about how to trouble care, Sonali thinks about care in ways that are not based in capitalist consumption and focuses on how to make space to care for others, not just herself.

For Elisabeth, troubling care starts with asking the question in an academic context, such as, “how can I make sure I do not leave the most marginalized behind?” Elisabeth reflected on how in a university setting, some staff members' work is not visible or appreciated, despite being so essential to the team. Elisabeth said that this underappreciation and power imbalance creates an environment of marginalization and discomfort that needs to be challenged. Therefore, troubling care to Elisabeth means acting from discomfort and digging deeper to think about what it shows and what we should be doing differently to overcome these imbalances.

4) Imagine and reflect on what a care-filled future would look like for you and your communities.

Kevin expressed how we are experiencing a crisis of consent. Part of this is that we step over our own consent by not setting healthy boundaries for ourselves. Therefore, a more caring future for Kevin would involve learning how to skillfully cultivate healthy boundaries and learning how to honour the boundaries of others. Kevin believes that if this skill set becomes culture, we can create a collective process of care that is normalized throughout our life.

Sonali’s care-filled future involves one without capitalism. She sees the need to abolish systems that prevent us from truly caring for each other. Sonali discussed how she has to work a job to meet her basic needs for survival. Yet, living this way does not allow people to care for themselves or others because everyone is too focused on meeting their own basic needs to care for others. Therefore, Sonali imagines introducing a care model that isn’t racist or profit driven, but one that is centered on people and their well-being.

Elisabeth’s care-filled future involves creating warm, welcoming, and reflective academic spaces where people collaborate instead of competing. It is a future where we welcome people who are underrepresented in university settings and reflect on the power relations that exist. This is centered around transnational relations in the hopes of creating a collaborative space where students, faculty and other staff members can grow together in solidarity.

Nasra believes a care-filled future is one where everyone has what they need to not only survive but thrive. It includes elements of consent and respecting boundaries that people are comfortable with to cultivate a collective care model. Nasra relates this to the social determinants of health framework, stating that this is important for promoting individual and population health and well-being. This means everyone has equitable access to shelter, housing, social supports, food, and that we create an anti-racist society through understanding the lived social realities of others.

Concluding Remarks

This conversation explored care across distinct and interconnected communities where care is being challenged and reimagined to be attuned to the needs of those around us, acknowledging the interdependence between all of us to create a collective form of care.

Event Transcript

View the full "A Community Conversation Troubling Care" transcript

Event Recording

View the "A Community Concersation: Troubling Care" recording

See below for links and resources provided during the webinar:

- Live Work Well Research Centre Integrating Care and Livelihoods Research Cluster: https://liveworkwell.ca/care

- Amy Kipp: www.researchingcare.ca | twitter @amykipp | akipp@uoguelph.ca

- Roberta Hawkins | rhawkins@uoguelph.ca

- Elisabeth Militz | twitter @ElisabethMilitz | https://geg.uoguelph.ca/post-doc/militz-elisabeth

- Guelph Neighbourhood Support Coalition: http://guelphneighbourhoods.org/

- Nasra Hussein | twitter @Nasrassistic | nasra.hussein@guelphneighbourhoods.org

- Kevin Sutton | visionwings@gmail.com

- ArtsEverywhere.ca Complicating Care Series: https://www.artseverywhere.ca/series/complicating-care/

- Sonali Menezes: instagram @sonaleeeeeee | https://www.artseverywhere.ca/depression-cooking/

- Aislinn Thomas: https://aislinnthomas.ca | https://www.artseverywhere.ca/maid-in-canada/